Dingy Butterflies takes its name from J B Priestley’s 1934 book ‘An English Journey’. For research he visited Bensham Grove Educational Settlement, Gateshead in 1933 and sat in on an unemployed men’s group. In the book he calls them the ‘Dingy Butterflies of the back streets’. Something for which he was heavily criticised for, though in recent years his thoughts have been seen more as a criticism of the government of the times treatment and abandonment of towns and villages, in particular in the North.

Bensham Grove is also where our first project ‘The Spence Watson Archive’ took place. We are inspired by Robert (1837-1911) and Elizabeth Spence Watson (1838-1919) who lived at Bensham Grove House from 1875 until 1919, before it became an educational settlement. They were Quakers and prominent social activists in Gateshead and Newcastle. The family valued education and social justice and were tireless campaigners for workers rights, women’s education, the anti-slave trade, and a lifelong interest in literature and the arts. It is these core values that Dingy Butterflies, as a creative organisation, take as its starting point.

Robert and Elizabeth Spence Watson

Robert Spence Watson was a Quaker and a Liberal who spent all his life championing the oppressed and working classes. He was a politician, an educator, as well as believer in the importance of the arts and creativity. He was involved in the Ragged and Industrial School and the ‘Climbing Boys Act of 1840’ and organised the ‘Shoe Black Brigade’, providing young boys from the streets with the equipment to clean shoes. He travelled extensively in the UK and Europe and beyond including mountaineering in Norway and the Alps, and solo-travelling across Morocco, which he wrote about in his 1880 book ‘A visit to Wazan, the sacred city of Morocco’.

Elizabeth Spence Watson, nee Richardson, was also active and heavily involved in women’s rights and educational reform. She was a governess of local girls schools, a Guardian of the Poor Law at Gateshead’s Workhouse and active in helping poor children into education. She was a key figure in the Women’s Franchise League, co-founder of the Newcastle and District Women’s Suffrage Society in 1900 and a council member of the North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage. She was active in peace activism protesting against the Boer War and presided over the Tyneside branch of the International Arbitration and Peace Association, supporting conscientious objectors during the First World War. One story goes that, during the First World War and when she was in the last few years of her life, she left her home to protect a German owned shop from an angry mob.

Both Robert and Elizabeth were heavily involved in fighting slavery alongside the Richardsons, Elizabeth’s family. In September 1875 Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli issued a circular to British ships ordering them to return any stowaway slaves to their owners. Robert called a meeting of the Newcastle Liberal Association announcing if any stowaway slave were returned, he would indict the ship’s captain for kidnapping and Disraeli as an accomplice. As a result Disraeli withdrew the circular.

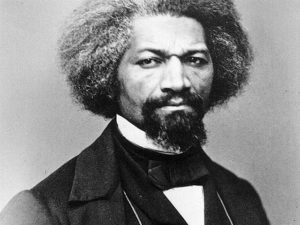

A lot of Robert Spence Watson’s beliefs can be traced back to his Grandfather, Joshua Watson (1771 – 1853) and Father, Joseph Watson (1807 – 1874) both also Quakers. Joseph Watson, in particular was an attorney and a political reformer who held strong views on civil and religious liberty and was a great believer in the abolition of slavery in America and the West Indies. He was known to welcome to his table at Bensham Grove, fugitive slaves including William Wells Brown (c.1814 – 1884) and Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895). This must have been something that influenced Robert’s life and beliefs as he grew up.

Frederick Douglass

Much has been written recently about Frederick Douglass and his time living in Newcastle at Summerhill with Elizabeth’s relatives Anna and Henry Richardson. Indeed he has had a blue plaque installed at the house in Summerhill and has recently had a £35 million Newcastle University building named after him not far from Summerhill.

Douglass was born into slavery in 1818 in Maryland and was an anti-slavery campaigner – and at the time of visiting the UK and the North East was an escaped slave himself. He was in Newcastle in 1846 as part of a lecture tour of Great Britain and Ireland during which he spoke to packed halls and churches about slavery in his native U.S.

While in Newcastle, Douglass stayed with Anna Richardson and her sister-in-law, Ellen, who lived on Summerhill Grove. The two Quaker women actively campaigned for a number of social causes, and raised £150 to buy his freedom. You can read more about him at the Friends of Summerhill.

William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown, a contemporary of Douglass, is not as well known today, at least in these parts. He was born into slavery in Kentucky in 1814. After several attempts in 1834 he escaped to Ohio and was took in by a Quaker called Wells Brown, which is where he took his name.

He spent the next few years helping other escaped slaves to get into Canada, where they could be safe. He became part of the national network of the ‘Underground Railroad’ offering help and assistance to fugitives along the way. He was a brilliant speaker and lecturer and supported causes including temperance, women’s suffrage, pacifism and prison reform. In 1849 he travelled to Britain remaining here until 1854, travelling across the country giving hundreds of lectures. It was again the Richardsons, as it was for Douglass, in Newcastle who purchased his freedom. His antislavery lectures in Europe inspired his book Three Years in Europe (1852), which was expanded as The American Fugitive in Europe (1855). It was whilst in Britain that he also published his novel Clotel (1853), which is considered the first published novel written by an African American.

With what is happening in the world, it has made me think about this time in Bensham, Gateshead when prominent figures from the American anti-slavery movement visited the UK and Newcastle, and sat at the table in Bensham Grove discussing the issues at hand with Joseph whilst a young Robert possibly looked on. Whilst this is something to be proud of and adds to the history of the area of Bensham showing it has a long history as a place of refuge for those escaping oppression. This doesn’t mean there isn’t more to do. We need to consider how we can support our BAME friends in our community and in the arts. One way of doing this is to know our history.

Comments are closed here.